The concept of mission has often been narrowly understood as a programmatic endeavor of the church—an organized effort to evangelize, plant churches, or engage in social justice. While these activities are significant, they risk obscuring the profound theological reality that mission is first and foremost God’s own activity. The missio Dei, or “mission of God,” originates not from human initiative but from the very being of the triune God. This divine mission is rooted in the eternal, relational dynamics of the Trinity, where the Father sends the Son, the Father and Son send the Holy Spirit, and the Triune God collectively sends believers into the world. This Trinitarian foundation reveals that God is fundamentally a “Relator”—a being whose essence is defined by communion, self-giving love, and outward movement. As we delve into this theological framework, we will explore how divine relationality forms the ontological basis for mission and how human estrangement stands in stark contrast to God’s redemptive invitation. This post will unpack the biblical narratives, related systematic theological categories, and missiological implications of this foundation, ultimately calling each believer to participate in God’s mission as a response to His divine love for each one of us.

The Trinitarian Foundation of Mission: God as Relator

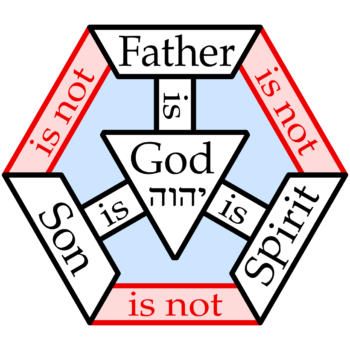

The doctrine of the Trinity teaches that God exists as three distinct persons—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit—who are co-equal, co-eternal, and united in one divine essence. This is not a static or abstract concept but a dynamic reality characterized by eternal relations of love and self-giving. The term “perichoresis” describes this mutual indwelling and interpenetration within the Godhead, where each person fully shares in the life of the others. This relational ontology is the wellspring of mission. In God, interaction and dialogue, communication and communion is so intense and complete that it overflows into the world and embraces all of humanity. The Trinity is, therefore, also mission—or God’s ongoing dialogue with humanity, inviting and drawing all of humanity into perfect communion with the divine community. This overflow of divine love is not an afterthought but the natural expression of God’s being. If God were not love, He would not need to be triune; He could exist as a solitary deity. But because God is love, He exists as a community where love is given and received.

all of humanity into perfect communion with the divine community. This overflow of divine love is not an afterthought but the natural expression of God’s being. If God were not love, He would not need to be triune; He could exist as a solitary deity. But because God is love, He exists as a community where love is given and received.

The Trinitarian foundation of mission is clearly articulated in the biblical narratives of sending. In John 20:21-22, Jesus commissions His disciples with the words, “Peace be with you! As the Father has sent me, I am sending you.” He then breathes on them, saying, “Receive the Holy Spirit.” This passage mirrors the Father’s sending of the Son and extends it to the disciples, empowered by the Spirit. Similarly, in John 14:26, Jesus promises that the Father will send the Holy Spirit in His name, highlighting the collaborative sending within the Trinity. John 17:18 further reinforces this pattern, as Jesus prays, “As you sent me into the world, I have sent them into the world.” These texts reveal that mission is not a human invention but a participation in the divine sending.

Systematically, this Trinitarian foundation connects to multiple theological categories. In Theology Proper, the doctrine of the Trinity emphasizes both the immanent relations (the eternal communion within the Godhead) and the economic actions (God’s redemptive work in history). The intra-Trinitarian sending grounds mission in God’s eternal essence, showing that the missio Dei is not an ad hoc plan but flows from who God is in Himself. Christologically, the Son’s mission from the Father reveals divine relationality through the incarnation, where the sent One accomplishes redemption. Pneumatologically, the Spirit’s procession and sending extends the intra-Trinitarian relations outward, empowering the individual believer’s participation. Ecclesiologically, the people of God are incorporated into this sending dynamic, existing as a sent community that reflects divine communion. Soteriologically, redemption is Trinitarian in structure—the Father’s plan, Son’s accomplishment, and Spirit’s application—framing mission as an invitation into the relational fellowship of the Godhead. Even the attributes of God, such as love and communion, inherently overflow in mission, making the Trinitarian foundation the ontological ground for divine self-giving.

Missiologically, this Trinitarian foundation establishes the ontological basis for mission, distinguishing it from ecclesiocentric (“church centered”) models that focus primarily on the church’s corporate activities. Missio Dei is the name given by theologians to the conception and practice of mission in a post-colonial world. Proposals related to missio Dei have appealed to and coincided with a rebirth in trinitarian theology. This shift relocates mission’s origin from human effort to God’s being, emphasizing that mission is first about who God is before it is about what the church does. The church, then, is not the initiator of mission but its instrument, called to participate in God’s ongoing redemptive work.

Divine Relationality in Mission: The Dynamics of Sending

The Trinitarian foundation of mission reveals God as a “Relator”—a being whose essence is defined by relationality and sending. This is not a distant or abstract relationality but an intimate, dynamic one that invites humanity into communion. The sending narratives in Scripture illustrate this beautifully. In John 20:21-22, Jesus’ commissioning of the disciples is a direct continuation of the Father’s sending of the Son. By breathing the Holy Spirit upon them, Jesus empowers them to participate in the same mission. This act of sending is not merely functional but deeply relational, as it invites the disciples into the divine life. Similarly, in John 14:26, the Father’s sending of the Spirit in the Son’s name underscores the collaborative nature of Trinitarian mission. The Spirit is not sent independently but in harmony with the Father and Son, ensuring that mission remains rooted in divine relationality.

John 17:18 further emphasizes this dynamic, as Jesus prays for His disciples to be sent into the world just as He was sent by the Father. This prayer reveals the missional heart of Jesus, who desires His followers to share in His mission. It also highlights the Trinitarian pattern of sending: the Father sends the Son, the Son sends the disciples, and all are empowered by the Spirit. This pattern is not a hierarchy but a harmony of distinct persons united in purpose. The persons of the Trinity simply are what they are in their relations to one another, which both distinguish them from one another and bring them into communion with one another. This relational unity in diversity is the model for all missional activity.

The implications of this Trinitarian sending are profound. First, it means that mission is rooted in God’s love. The Father sends the Son out of love for the world; the Son sends the disciples out of love for the Father and the world; the Spirit empowers mission out of love for the Father and Son. This love is not sentimental but self-giving and sacrificial. Second, it means that mission is participatory. Believers are not passive observers but active participants in the divine mission. As Christians are included in the Triune life and participate in the divine nature of God, they are included in, and actively participate in, his divine mission. This participation is not about becoming a “fourth member” of the Trinity but about being incorporated into the Trinitarian life and sentness. Third, it means that mission is communal. The Trinity is a community of love, and mission reflects this communal nature. Believers are called to embody this communion in their missional activities, fostering unity and reconciliation in a fragmented world.

Missiologically, this Trinitarian sending challenges functional or pragmatic approaches to mission. Instead of focusing solely on strategies or results, it calls believers to prioritize relationality—both with God and with others. God is, therefore, social and is defined by the communion (perochoresis) of three persons. This social nature of God invites believers to engage in mission as a relational enterprise, where love, dialogue, and communion are central. It also means that mission is not just about proclaiming the gospel but about embodying it—inviting others into the relational life of the Trinity.

Human Estrangement: The Response of Non-Believers

While the Trinitarian foundation of mission reveals God’s relational invitation, the response of non-believers often manifests as estrangement. This estrangement is not merely a lack of belief but a conscious or unconscious rejection of the communal bonds offered by the Triune God. It is a turning away from the divine invitation into fellowship, resulting in isolation from God and others. This response is rooted in sin, which fractures relationships and leads to autonomy, idolatry, and self-imposed separation. Out of his dynamic love, God created all that exists. He created humanity, the apex of his creation, in his image, to live in communion with him. However, humanity’s fall into sin disrupted this communion, leading to estrangement.

The biblical narrative illustrates this estrangement from the beginning. In Genesis 3, Adam and Eve’s disobedience leads to alienation from God and each other. This pattern continues throughout Scripture, as humanity repeatedly rejects God’s relational invitations. In the New Testament, Jesus’ encounters with religious leaders and skeptics often highlight this resistance. For example, in John 3:19-20, Jesus explains, “This is the verdict: Light has come into the world, but people loved darkness instead of light because their deeds were evil. Everyone who does evil hates the light, and will not come into the light for fear that their deeds will be exposed.” This passage reveals that estrangement is not just a passive state but an active preference for darkness over the relational light of God.

Human estrangement manifests in various forms. One is resistance, where sinful autonomy leads to opposition against God’s mission. This can be seen in cultural idolatry, where human achievements or ideologies are elevated above God, or in persecution of those who bear witness to the gospel. Another form is indifference, where apathy toward the gospel reflects a failure to recognize God’s redemptive outreach. This is often rooted in a prioritization of self over divine invitation, leading to a life lived as if God does not exist. Isolationism is another response, where a preference for individualism rejects the communal essence of Trinitarian life and mission. This is particularly prevalent in Western cultures, where personal autonomy is often valued above communal responsibility.

Relational brokenness is a further manifestation of estrangement. Fractured human bonds mirror the rejection of divine relationality, perpetuating conflict, loneliness, and injustice. In a world where the Trinity models perfect communion, human estrangement stands as a stark contrast. Finally, denial of communion reflects a skepticism toward intimate divine-human fellowship. This dismissal of the Trinitarian invitation as illusory or unnecessary is often rooted in a rationalistic worldview that rejects the supernatural or the relational nature of God.

Despite this estrangement, the missio Dei remains unrelenting. God’s mission is not thwarted by human resistance but continues to invite humanity into reconciliation. The Trinity is, therefore, also mission—or God’s ongoing dialogue with humanity, inviting and drawing all of humanity into perfect communion with the divine community. This invitation is extended through the community of Christian believers, which is called to embody the relational life of the Trinity and witness to God’s redemptive love. The church’s mission, then, is not just to proclaim the gospel but to demonstrate the reality of Trinitarian communion through love, unity, and reconciliation.

The Role of Believers: Participating in the Trinitarian Mission

The Trinitarian foundation of mission calls each believer to participate in God’s redemptive work. This participation is not about adding to God’s mission but about being incorporated into it. As Christians are included in the Triune life and participate in the divine nature of God, they are included in, and actively participate in, his divine mission. This participation is both a privilege and a responsibility, as believers are called to embody the relational life of the Trinity in their missional activities.

One way believers participate is through proclamation. The Great Commission in Matthew 28:18-20 calls believers to “go and make disciples of all nations, baptizing them in the name of the Father and of the Son and of the Holy Spirit.” This commission is Trinitarian in its formula and in its foundation, as it flows from the authority of the Triune God. Proclamation, however, is not just about words but about embodying the gospel through love and service. The church, therefore, participates in the mission of God, which is rooted in the Trinitarian communion of love. This means that evangelism must be relational, inviting others into the communion of the Trinity rather than simply presenting a set of beliefs.

Another way believers participate is through justice and reconciliation. The Trinitarian foundation of mission emphasizes God’s concern for all of creation, not just individual souls. This means that mission includes working for justice, peace, and reconciliation in a broken world. The Trinity is, therefore, also mission—engaging in an ongoing dialogue with humanity, inviting and drawing all of humanity into perfect communion with the divine community. This invitation extends to societal structures, as believers are called to confront systems of oppression and reflect the justice of the Trinity in their communities.

Believers also participate through community. The Trinity is a model of perfect communion, and the church is called to reflect this in its life together. This means fostering unity amid diversity, love amid conflict, and humility amid pride. The persons simply are what they are in their relations to one another, which both distinguish them from one another and bring them into communion with one another. This relational unity is a powerful witness to the world, as it demonstrates the reality of Trinitarian life.

Finally, believers participate through worship. Trinitarian worship is not just a liturgical exercise but a missional activity, as it renews and propels the church’s sentness. Worshiping the Triune God aligns believers’ hearts with His mission and empowers them to live out His relational love in the world.

Overcoming Estrangement: The Church’s Missional Witness

The church’s role in overcoming human estrangement is central to the Trinitarian mission. As the sent community, the church is called to embody the relational life of the Trinity and invite others into communion with God. This witness is both prophetic and practical, as it confronts estrangement while demonstrating reconciliation.

One aspect of this witness is prophetic. The church is called to speak against the idols and ideologies that foster estrangement. This includes challenging individualism, materialism, and relativism, which lead to isolation and brokenness. The church’s prophetic witness reminds the world of this original design and calls it back to relational communion.

Another aspect is practical. The church is called to demonstrate reconciliation through its actions. This includes working for justice, serving the poor, and fostering unity amid diversity. This work is not just verbal but embodied, as the church lives out the reality of Trinitarian love in its relationships and ministries.

The church’s witness is also communal. By living as a relational community, the church models the Trinitarian life and invites others into it. This means practicing hospitality, forgiveness, and mutual care. This communal witness is a powerful antidote to estrangement, as it offers a tangible experience of divine fellowship.

Finally, the church’s witness is sacramental. Through practices like baptism and communion, the church participates in the Trinitarian life and invites others to do the same. These sacraments are not just symbols of saving faith, but also a reminder of the “means of grace,” where believers encounter the relational presence of the Triune God.

Conclusion: The Call to Trinitarian Mission

The Trinitarian foundation of mission reveals that God is a Relator— a being whose essence is defined by communion, self-giving love, and outward movement. This divine relationality is the wellspring of the missio Dei, inviting humanity into fellowship with the Triune God. Human estrangement stands in contrast to this invitation, manifesting as resistance, indifference, and isolation. Yet, the church, as the sent community, is called to participate in God’s mission by embodying Trinitarian love, proclaiming the gospel, and working for reconciliation.

This understanding of mission has profound implications for every believer. It calls us to move beyond programmatic or functional approaches to mission and to prioritize relationality—both with God and with others. It reminds us that mission is not just about what we do but about who we are in Christ. Our participation in the mission of God is a privilege and a responsibility, as we are invited to share in the divine life and to extend its relational love to a world marked by estrangement.

In a world where alienation and brokenness abound, the Trinitarian foundation of mission offers a message of hope. It reminds us that God’s mission is one of reconciliation, inviting all of humanity into the communion of the Trinity. As believers, we are called to embody this mission, to live as relational communities, and to extend the love of the Triune God to every corner of creation. This is the heart of the missio Dei— a mission rooted in the eternal love of the Father, accomplished by the sent Son, and empowered by the Spirit. May we answer this call with joy and faithfulness, participating in God’s mission until the day when all of creation is drawn into perfect communion with the Triune God.

Sources

-

Bosch, D. J. (2011). Transforming Mission: Paradigm Shifts in Theology of Mission. American Society of Missiology Series.

-

Barth, K. (1956). Church Dogmatics, Vol. I, Part 1: The Doctrine of the Word of God. T&T Clark.

-

Wright, C. J. H. (2006). The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative. IVP Academic.

-

Flett, J. G. (2010). The Witness of God: The Trinity, Missio Dei, Karl Barth, and the Nature of Christian Community. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

-

Newbigin, L. (1995). The Open Secret: An Essay on the Christian Approach to Other Religions. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co.

-

Stott, J. R. W. (1995). Christian Mission in the Modern World. IVP Academic.

Dr. Curt Watke is a distinguished missiologist whose three-plus-decade-long career has significantly impacted Christian mission work in North America, particularly in under-reached and challenging regions. Holding a Ph.D. in Evangelism and Missions, Dr. Watke has focused on bridging cultural gaps and fostering sustainable Christian communities by developing innovative strategies that address contemporary challenges like globalization, urbanization, and religious pluralism. His emphasis on cultural sensitivity and contextualization in mission work is reflected in his collaborative writings, including notable works such as “Ministry Context Exploration: Understanding North American Cultures” and “Starting Reproducing Congregations.” Beyond his writing, Dr. Watke is a sought-after speaker and educator, lecturing at seminaries and conferences worldwide, and his teachings continue to inspire and equip new generations of missional leaders. His enduring legacy is marked by unwavering dedication to the mission of God and a profound influence on missional thought and practice. Dr. Watke serves as President and Professor of Evangelism & Missiology at Missional University.