In our search for meaning, we often try to write our own story. We craft narratives of self-made success, personal fulfillment, and individual destiny, believing we are the sole authors of our lives. But the Bible presents a different reality. It reveals that we are not the authors but characters in a much grander, more epic story—a divine drama with a beginning, a middle, and an end. This is the biblical narrative framework, the overarching story of creation, fall, redemption, and consummation. Understanding this framework is not merely an academic exercise; it is the key to unlocking our true purpose. It reveals that God, the great Author, is on a mission to restore His creation, and our individual calling is to find our place in His redemptive story. This divine narrative, however, is met with a pervasive and persistent human response: arrogation, the arrogant attempt to seize the author’s pen and redefine reality on our own terms. This post will explore the profound tension between God’s creative narrative and human arrogation, and how understanding this dynamic clarifies our role in His mission.

The Grand Metanarrative: Mission as the Plotline of Scripture

Before we can understand our role, we must grasp the story itself. A robust theology of mission, rooted in the missio Dei (the mission of God), sees mission not as a series of isolated events but as the central plotline of the entire biblical narrative. God’s sovereign, redemptive purpose for creation is revealed progressively through Scripture, forming a cohesive and compelling story. This is what theologians call a “redemptive-historical” or “biblical-theological” approach. It insists that we cannot understand mission by simply compiling proof-texts; we must understand it as the unfolding drama of God’s action in history.

This grand metanarrative provides the essential framework for everything we do. It gives our lives context, direction, and hope. As Christopher J.H. Wright argues in his seminal work, The Mission of God, the Bible’s own grand narrative should be the primary hermeneutical key for understanding our mission. When we see mission as the thread that ties the whole Bible together, from Genesis to Revelation, we begin to see that it is not our project but God’s. It is the story of His relentless pursuit of restoring all that was lost in the fall.

This four-chapter framework—Creation, Fall, Redemption, and Consummation—is more than a theological outline; it is the very structure of reality. It is the story God is writing in the world, and our lives are a part of it. To understand our individual calling, we must first understand the plot of the story in which we live. It is a story that begins in perfect harmony, plunges into tragic brokenness, is redeemed by sacrificial love, and culminates in glorious restoration. Our purpose is found not in writing a competing story, but in entering into this one as faithful characters.

Chapter One: Creation – The Foundation for Mission in a Good World

The story begins, as all good stories do, at the beginning. Genesis 1 and 2 paint a breathtaking picture of God’s original creation. He speaks, and a universe bursts into existence. He forms, fills, and fashions a world that is “very good” (Genesis 1:31). It is a world of perfect order, harmony, and shalom—peace, wholeness, and flourishing. In this pristine environment, God creates humanity in His own image, giving them a unique and exalted role. He blesses them and gives them a mandate: “Be fruitful and increase in number; fill the earth and subdue it. Rule over the fish in the sea and the birds in the sky and over every living creature that moves on the ground” (Genesis 1:28).

This is often called the “cultural mandate,” and it is the foundation for all human endeavor. As image-bearers, we were created to work, to create, to cultivate, and to steward God’s good world on His behalf. We were His representatives, His vice-regents, tasked with extending the borders of the Garden and turning the whole world into a sanctuary of worship and delight. In this original state, there was no “mission” as we think of it today, because there was no brokenness to fix, no lostness to address. There was only the joyful task of participating in God’s ongoing creative work, of developing the potential He had embedded in His creation.

This first chapter is crucial for our understanding of mission because it establishes the goal. Mission is not about escaping the material world or retreating into a purely spiritualized existence. It is about the restoration of God’s original good intentions for His creation. The goal of redemption is to get us back to the garden, and then beyond, to the glorious city of God. As N.T. Wright often emphasizes, the Christian hope is not for life after death, but for life after life after death—a resurrected life in a renewed creation. Therefore, our mission must be holistic. It must address the spiritual brokenness of the fall but also the social, cultural, and physical brokenness that mars God’s good world. We are called to be agents of new creation, pointing forward to the day when all things will be made new.

Chapter Two: The Fall – The Disruption that Necessitates Mission

The harmony of creation is shattered in Genesis 3. The fall of humanity into sin is not just a minor plot twist; it is a cataclysmic event that disrupts every dimension of reality. It is a rebellion against the Creator’s authority, an attempt to usurp His role and define good and evil for ourselves. The consequences are devastating and far-reaching. The relationship between God and humanity is broken, leading to alienation and spiritual death. The relationship between human beings is broken, leading to shame, blame, and conflict. And humanity’s relationship with the created order is broken, as the ground is cursed and creation itself is subjected to frustration.

This is the reason mission exists. The fall introduces the problem that mission is designed to solve. Sin is not just a personal moral failing; it is a cosmic power that has enslaved humanity and corrupted the entire created order. It is the source of all the pain, suffering, injustice, and futility we see in the world. The apostle Paul describes this cosmic scope in Romans 8:19-23: “We know that the whole creation has been groaning as in the pains of childbirth right up to the present time. Not only so, but we ourselves, who have the firstfruits of the Spirit, groan inwardly as we wait eagerly for our adoption to sonship, the redemption of our bodies.”

This passage is a profound theological statement about the context of our mission. It tells us that creation itself is caught up in the drama of redemption. The natural world is not just a passive backdrop for human history; it is an active participant, groaning for liberation from the bondage to decay brought about by human sin. This radically expands our understanding of mission. It is not just about saving “souls” to escape a doomed earth. It is about participating in God’s liberating work for all of His creation. It is about bringing healing and wholeness to broken people, broken relationships, and broken systems. The fall is the reason the world needs missionaries, doctors, counselors, artists, justice-seekers, and environmental stewards who are working to reverse the effects of the curse and point forward to the coming restoration.

Chapter Three: Redemption – God’s Missional Initiative in History

In the face of this cosmic rebellion, God does not abandon His creation. He does not erase the story and start over. Instead, He launches the most ambitious and costly rescue mission in history. This is the third chapter of the story, the chapter of redemption, and it is the very heart of the missio Dei. From the moment of the fall, God begins to reveal His plan to reconcile all things to Himself.

This redemptive mission unfolds progressively throughout the Old Testament. God calls Abraham and promises that through his offspring, all nations on earth will be blessed (Genesis 12:3). He delivers Israel from slavery in Egypt and gives them His law, establishing them as a kingdom of priests and a holy nation, a light to the Gentiles (Exodus 19:6). He sends prophets to call His people back to faithfulness and to promise a coming Messiah who will bring ultimate salvation and justice. Each of these acts is a sovereign initiative, a foretaste of the great redemption that is to come.

The climax of this redemptive mission is found in the person and work of Jesus Christ. In the incarnation, the Creator God enters His own creation, taking on human flesh to dwell among us. He is the perfect image-bearer, the faithful Israelite, the promised Messiah. In His life, He embodies the reign of God, demonstrating what it looks like to live in perfect harmony with the Creator’s will. In His death on the cross, He takes the full penalty for our sin, breaking the power of evil and reconciling us to God. In His resurrection, He conquers death and launches the new creation, guaranteeing the future renewal of all things.

Jesus’ life, death, and resurrection are the center of God’s redemptive story. They are the decisive act through which God is reversing the effects of the fall. And He commissions His followers to participate in this mission. The Great Commission (Matthew 28:18-20) is not a new mission but a call to participate in the mission Jesus has already accomplished. We are sent to make disciples, to baptize, and to teach, to be the heralds of the good news that the God who created this world has redeemed it through His Son. Our individual calling is rooted in this chapter of redemption. We are called to be ambassadors of Christ, as 2 Corinthians 5:20 says, “as though God were making his appeal through us.” We are to proclaim the gospel, the power of God for salvation to everyone who believes. But our mission is not limited to proclamation. It is also about embodiment. We are to be agents of reconciliation, healing, and justice in a broken world, living out the reality of the kingdom that Jesus inaugurated. We are to be the “firstfruits” of the new creation, communities that give the world a foretaste of the restored relationships and flourishing that God intends for all of creation.

Chapter Four: Consummation – The Goal and Motivation for Mission

Every good story needs a satisfying ending, and the Bible’s story has the most glorious ending imaginable. The final chapter is consummation, the picture of God’s mission brought to its ultimate completion. The book of Revelation gives us a breathtaking vision of this future reality. It is a vision of a new heaven and a new earth, where God dwells with His people in perfect harmony (Revelation 21:1-3). In this new creation, there is no more death, mourning, crying, or pain. The curse is completely reversed. The city of God, the New Jerusalem, is described as a place of perfect beauty, justice, and peace, a place where the river of life flows and the tree of life bears fruit for the healing of the nations (Revelation 22:1-2).

This eschatological hope is not just a nice thought to comfort us in difficult times. It is the telos, the goal, of our mission. It is the “why” behind everything we do. We work for justice now because we know that perfect justice will one day be a reality. We pursue reconciliation now because we know that perfect reconciliation will one day be achieved. We care for creation now because we know that creation will one day be fully renewed. Our present actions are motivated and shaped by our future hope. We are living in the “already” of God’s kingdom while pointing forward to the “not yet” of its full consummation.

This future hope gives our mission a profound sense of confidence and perseverance. We know that our work is not in vain. We are laboring for a reality that God Himself has promised and is guaranteed to bring about. As Paul says in 1 Corinthians 15:58, “Therefore, my dear brothers and sisters, stand firm. Let nothing move you. Always give yourselves fully to the work of the Lord, because you know that your labor in the Lord is not in vain.” The consummation is the guarantee that God’s mission will succeed. Our role is to be faithful agents in the present, working in alignment with His ultimate purposes for the future.

The Human Response: Arrogation – Seizing the Author’s Pen

If God’s creative narrative is the overarching plotline of history, then humanity’s consistent response is a tragic subplot of arrogation. To arrogate is “to take or claim (something) for oneself without justification.” In the context of God’s story, human arrogation is the attempt to seize the author’s pen, to usurp the Creator’s prerogative, and to rewrite the narrative on our own self-centered terms. It is the rebellion of Genesis 3 replayed in every generation and in every human heart.

This arrogation takes many forms, but at its core, it is a rejection of God’s authority and a denial of His story. One of the most common forms is the arrogation of meaning. In a world created by God for His purposes, the rebel heart insists on creating its own meaning and purpose. This is the essence of secular humanism, the belief that humanity is the measure of all things. It is the attempt to find fulfillment in career, wealth, relationships, or self-actualization, while ignoring the God who gave us those gifts and the story in which they find their true purpose. As the book of Ecclesiastes so poignantly illustrates, a life lived “under the sun,” apart from God’s narrative, is a life of “vanity” and futility (Ecclesiastes 1:2).

Another form of arrogation is the exploitation of creation. The cultural mandate given in Genesis was a call to steward God’s good world on His behalf. But in our fallen state, we have twisted it into a license to exploit. We ravage the environment, consume resources with reckless abandon, and treat the natural world as an object to be used for our own profit and pleasure, rather than a gift to be cared for. This is a direct rebellion against our creational purpose and a perpetuation of the brokenness that God is seeking to redeem. It ignores the groaning of creation and our role as its potential liberators.

Perhaps the most subtle form of arrogation is the denial of the fall itself. In our attempt to write our own story, we often minimize or deny the reality of sin and brokenness. We try to convince ourselves that humanity is basically good and that our problems can be solved through better education, social programs, or technological innovation. While these things are good and necessary, they can never address the root problem of the human heart. To deny the depth of the fall is to deny the need for a divine Redeemer. It is to insist that we can write our own happy ending without the Author of life. This is the ultimate act of arrogance, and it keeps us trapped in the very brokenness we refuse to acknowledge.

Our Individual Calling: Finding Our Role in God’s Story

In light of this great cosmic drama between God’s creative narrative and human arrogation, what is our individual calling? The answer is clear: we are called to lay down our own pens, to reject the arrogance of self-authorship, and to embrace our God-given role in His story. We are called to be faithful characters in the divine drama, not rebellious authors trying to write our own competing script.

This begins with a radical reorientation of our identity. We must stop seeing ourselves as the center of our own stories and start seeing ourselves as characters in God’s story. Our primary identity is not our job, our nationality, our social status, or even our personal achievements. Our primary identity is “child of God,” “image-bearer,” “disciple of Jesus,” “ambassador of Christ,” “agent of new creation.” When we truly understand who we are in God’s story, it changes everything about how we live. It gives us a new sense of purpose, a new set of priorities, and a new source of power.

This reorientation leads to a life of participation. We are called to actively participate in the redemptive chapter of the story. This means we must be about the business of reversal. Where we see brokenness, we are called to bring healing. Where we see injustice, we are called to bring righteousness. Where we see division, we are called to bring reconciliation. Where we see despair, we are called to bring hope. This is not just the job of pastors and missionaries; it is the calling of every single follower of Jesus. A teacher who sees her work as shaping the next generation to think God’s thoughts after Him is participating in God’s story. A business owner who runs his company with integrity and seeks to create value for his employees and community is participating in God’s story. A parent who raises his children to know and love the Lord is participating in God’s story. An artist who creates beauty that reflects the glory of the Creator is participating in God’s story.

Finally, our calling is one of anticipation. We are to live as people who are caught between the “already” of Christ’s redemptive work and the “not yet” of its final consummation. We are to be a people of hope, living in the light of the future that God has promised. This hope should not lead to passivity but to passionate, expectant action. We work for justice now because we know that perfect justice is coming. We pursue reconciliation now because we know that perfect reconciliation is the future. We care for this world now because we know it will one day be renewed. Our lives should be a foretaste of the coming kingdom, a preview of the new creation, a signpost pointing to the day when God’s story will reach its glorious end and all things will be made new.

Conclusion: Living in the Great Story

The choice before each of us is clear. We can either live in the small, cramped, and ultimately futile story of our own arrogation, or we can enter into the grand, epic, and eternally significant story of God’s creative narrative. We can continue to seize the pen, trying to write a story where we are the hero, the author, and the ultimate authority. Or we can surrender the pen to the one true Author and discover the joy and purpose of being a character in His magnificent drama.

To live in God’s story is to see everything differently. It is to see our work not as a means of self-fulfillment but as an act of worship and stewardship. It is to see our relationships not as a network for personal advantage but as opportunities for love and reconciliation. It is to see our resources not as our own possession but as a trust to be used for the advancement of God’s kingdom. It is to see our lives not as a random series of events but as a meaningful part of God’s unfolding plan to restore all things.

This is the high and holy calling of every believer. It is not a burden to be endured but a privilege to be embraced. Let us, therefore, lay down our arrogance, pick up our cross, and follow the Author of life into the great story He is writing. Let us find our place in His mission of redemption, and let us live with the confident hope that the story we are in is the greatest story ever told, and it is moving toward a conclusion more glorious than we can possibly imagine. Our individual lives, when surrendered to His narrative, gain a weight of glory that will echo into eternity. We are not just living; we are participating in the very renewal of all things, and in that, we find our truest and most profound identity.

Sources

-

Wright, Christopher J. H. The Mission of God: Unlocking the Bible’s Grand Narrative. IVP Academic, 2006.

-

Wright, N. T. Surprised by Hope: Rethinking Heaven, the Resurrection, and the Mission of the Church. HarperOne, 2018.

-

Barth, Karl. Church Dogmatics, Vol. III, Part 1: The Doctrine of Creation. T&T Clark, 1958.

-

Vanhoozer, Kevin. The Drama of Doctrine: A Canonical-Linguistic Approach to Christian Theology. Westminster John Knox, 2005.

-

Bavinck, Herman. Reformed Dogmatics, Vol. 2: God and Creation. Edited by John Bolt, translated by John Vriend, Baker Academic, 2004.

-

Van Engen, Charles E. Mission on the Way: Issues in Mission Theology. Baker Book House, 1996.

-

Schaeffer, Francis A. Genesis in Space and Time: The Flow of Biblical History. InterVarsity Press, 1972.

-

Newbigin, Lesslie. The Gospel in a Pluralist Society. Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 1989.

-

Heltzel, Peter G. Jesus and Justice: Evangelicals, Race, and American Politics. Yale University Press, 2009.

-

The Holy Bible, New International Version. Zondervan, 2011.

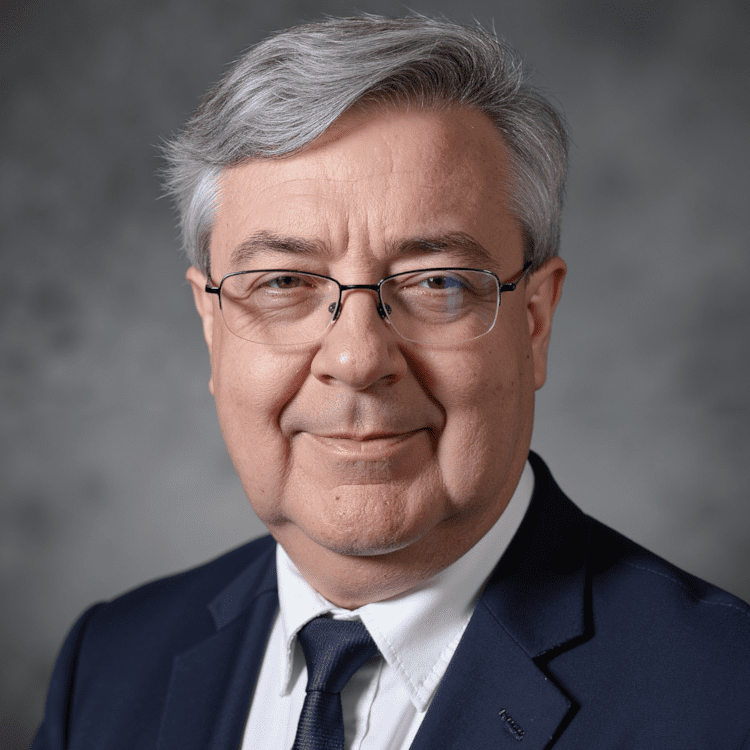

Dr. Curt Watke is a distinguished missiologist whose three-plus-decade-long career has significantly impacted Christian mission work in North America, particularly in under-reached and challenging regions. Holding a Ph.D. in Evangelism and Missions, Dr. Watke has focused on bridging cultural gaps and fostering sustainable Christian communities by developing innovative strategies that address contemporary challenges like globalization, urbanization, and religious pluralism. His emphasis on cultural sensitivity and contextualization in mission work is reflected in his collaborative writings, including notable works such as “Ministry Context Exploration: Understanding North American Cultures” and “Starting Reproducing Congregations.” Beyond his writing, Dr. Watke is a sought-after speaker and educator, lecturing at seminaries and conferences worldwide, and his teachings continue to inspire and equip new generations of missional leaders. His enduring legacy is marked by unwavering dedication to the mission of God and a profound influence on missional thought and practice. Dr. Watke serves as President and Professor of Evangelism & Missiology at Missional University.